App Directory Overview 2.0

An application directory (appD) is a structured repository of information about apps that can be used in an FDC3-enabled desktop. In other words, it’s a convenient way of storing and managing metadata about apps in your ecosystem.

The application metadata stored in appD records may include: the app name, type, details about how to run the application, its icons, publisher, support contact details and so on. It may also include links to or embed manifest formats defined elsewhere, such as proprietary manifests for launching the app in a container product or a Web Application Manifest (as defined by the W3C).

All this information is readily available in one place and can be used both to populate a launcher or app catalog UI for your users, and by the Desktop Agent managing the apps on your desktop. In fact, if your desktop platform supports the FDC3 standard, appD is the primary way that the FDC3 Desktop Agent implementation should receive the details about apps available to run on your desktop. Conversely, if an app is not listed in appD, the Desktop Agent can’t ensure its participation in context sharing or use it to resolve intents.

Advantages

Using appD offers many advantages both for financial institutions running an FDC3-enabled desktop container and for vendors that provide FDC3-compliant apps:

For the user

Easier to Find App Info

Your appD is the one place to collect all the information about apps. The more apps you have, the more you’ll appreciate the convenience of not having to chase down details about each. This is particularly important for large institutions with multiple desks.

Human Readable

AppD has two types of users. One is the Desktop Agent, but the other is humans administrating and using the smart desktop at your organization. Hence, an appD contains information about apps in both machine- and human-readable forms. For example, it includes both unique identifiers for apps that are used to refer to them in code and human-friendly app names, icons, descriptions and tooltips necessary to populate a launcher menu or app catalog user interface for your users.

Apps are Discoverable

For large institutions, it can be difficult to keep track of all the apps (developed both in-house and by vendors), since a typical desktop could have many. Users can search appD to discover the apps they need. An app might already reside on their system or be available to them over the internet, but if they don’t have a way to search the apps available to them, they won’t be able to find it. An appD provides a way for users to discover the apps they need.

An appD makes it possible to discover info about apps that reside on various domains, not just the one domain the appD itself is hosted on. In addition, you can find details about how to launch the apps in multiple, diverse environments. This is a different use-case to, for example, the W3C's Web App Manifest, which is hosted on the same domain as the app, is limited to web apps, and is generally used to 'install' an app that the user has already accessed.

Updating Apps

Typically, software evolves over time. The app versions you are running today will not be the same ones you need tomorrow. Therefore, you will need to upgrade apps periodically. Very few people look forward to upgrading, but appD and web deployment can make it easier for you. To roll out a new version of your app, either update the existing entry for it in appD or add a new entry for that version (allowing users to select the version they will use).

Agent-agnostic

As a part of the FDC3 standard, appD isn't tied to any specific vendor. This is important, as it allows you more flexibility in that you are not tied to any specific container or Desktop Agent implementation. If at any point you want to switch to a different Desktop Agent, the process won’t be prohibitively difficult. The existing appD will work without any additional effort from you, as long as your new Desktop Agent is also FDC3-compliant. This is in contrast with proprietary solutions, where you would have to produce a new configuration and integration for every application.

AppD reduces fragmentation in the market and allows end-users more flexibility in what applications can be included in their desktop.

Intent Resolution

AppD provides information to the Desktop Agent on which applications can handle particular intents and the context types they support as input to them. This allows the Desktop Agent to implement an intent resolver that can launch applications and pass the intent and context to them to operate on, supporting workflows between applications that didn't require prior bilateral agreements between the application providers.

For an Application Provider

Until now, we've looked at appD from the perspective of a desktop owner and user. But appD also offers advantages to vendors who develop apps for the financial services desktop.

Apps Work Well Together Out-of-the-box

When your customers add your FDC3-compliant app to their desktop via an appD record accurately describing it, you can be sure that your app will interoperate with other apps that follow the FDC3 standard. You don’t have to do anything special, or arrange a bilateral agreement with anyone else. The benefit of the open standard is that any app that follows it will work well with any other compliant app.

Easy Updates

As a vendor, you prefer for all your customers to run your latest software. However, many customers will postpone upgrades, sometimes for a long time, because upgrading can be a pain. An advantage of a vendor-hosted appD is that the configuration of an app can be updated at any time and, if your customers need to choose when to upgrade, multiple versions of it can be made available, each with their own configuration. By making it easier for customers to update, you can drive better adoption.

For the Industry

By hosting our own appD we can easily combine applications from various providers into one cohesive directory. Alternatively, we can connect to directories from multiple providers (in standardized format) and provide a single view over them. This reduces fragmentation in the market, allows end-users more flexibility in what apps to include in their smart desktop, and obviates the need for vendors to provide application details in diverse formats or for their customers to work out these details for themselves.

Relationship to Other Standards

The App Directory's application record is similar to application manifests defined in other standards, in particular the W3C's Web Application Manifest. However, the App Directory, and by extension the application record, serve a different set of use-cases specific to application interoperability on financial services desktops, which other standards do not fully address.

Wherever possible, FDC3 seeks to draw inspiration from, align itself with and reference other standards - ensuring that conventions and best practices developed by those standards are reused, along with the standard itself (e.g. data formats in ISO standard formats, external links to technology-specific manifest file formats etc.). For a list of standards that FDC3 references, see the References page.

Use Cases

An application directory provides information about an application's identifiers, publisher details, intents that it supports, and metadata necessary to launch and integrate the application in a Desktop Agent.

The following provides a summary of use cases.

Launcher

A Desktop Agent will usually include a user interface allowing the user to select from a set of launchable applications and then allow them to manually launch one. It is also responsible for launching applications necessary to resolve a raised intent. However, it must first retrieve the necessary metadata about the available applications. An app directory provides an endpoint to retrieve a list of the available applications along with their metadata, which may include or link to additional information necessary to launch the application in a specific Desktop Agent.

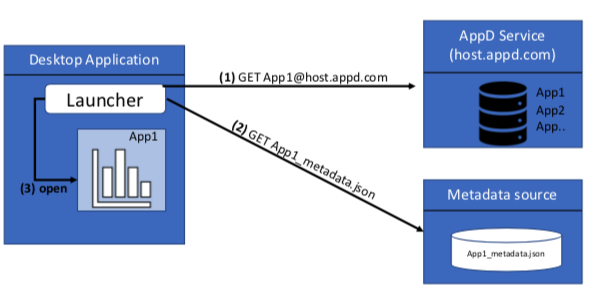

A launcher will usually be configured with the locations of one or more AppD servers (which is necessary to implement intent resolution), however, as described in the Service Discovery section, a fully qualified application identifier (app1@host.appd.com) may also be used to both locate the appD service and to retrieve the specific application data.

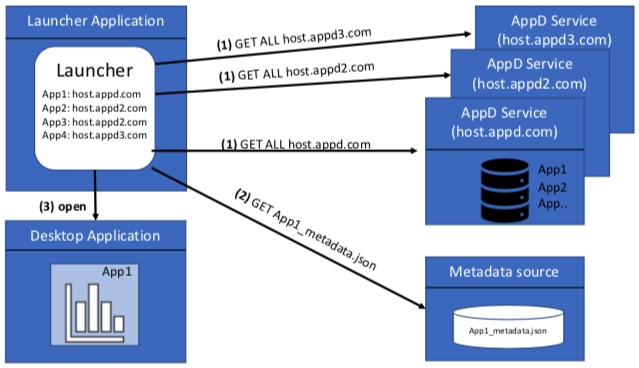

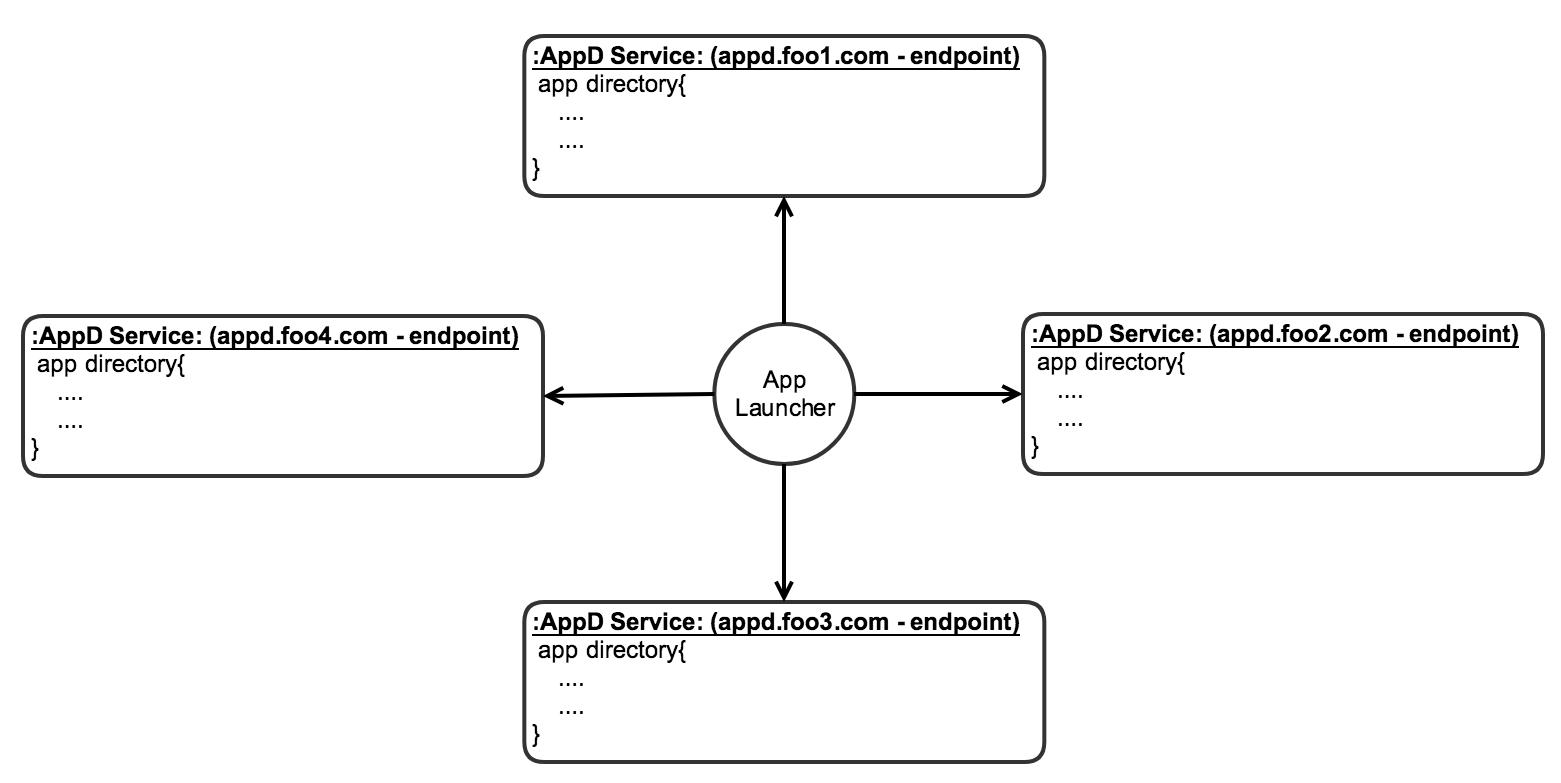

Aggregated View

There could be many different appD service instances in the world providing application data zoned to the provider or enterprise deployment. The appD specification allows for unique instances of the service with no requirement to aggregate data or define a structured hierarchy. With this said, a launcher might want to construct an aggregated view of applications from one or more appD instances. In this case, the launcher would be required to retrieve multiple application definitions from one or more appD instances providing a consolidated view of all applications required.

Today, there is no intention to create a single registry of known AppD instances, so there is an assumption that the launcher will have prior knowledge of the AppD instance location.

Authentication and Entitlements

The AppD API specification defines the optional use of an access token to identify the requesting user/launcher and implement authorizations which may affect appD API responses. For example, different subsets of the full list of applications may be returned for different users depending on their role in an organization.

The specification does not define or make mandatory any authorizations or roles that a provider or enterprise can define.

Application Identifiers

Application Records served by an app directory are each labelled with an identifier, appId, which should be unique within the app directory instance and may be used to refer to or retrieve the application's record via the app directory API. This identifier may be made globally unique through a nested namespace approach and email address construction (appId@fqdn) where @ followed by the app directory instance's host name is appended to it. The resulting globally unique identifier is known as a 'fully qualified application identifier'.

Fully qualified appIds may be used to locate the appD instance hosting the application's record. See the Service Discovery section for details.

Shrinking the URI

Although the concept of fully qualified application IDs are useful in resolving the actual host of the application directory, there is no requirement for an application directory to use this fully qualified application ID as the resolver for a record. An application ID is unique to given application directory, but there is no requirement to use the fully qualified representation when querying an interface. Taking the prior example, the fully qualified application ID "app1@appd.foo.com" is represented as "app1" within the application directory. As a result a launcher can use a shortened URI construct "https://appd.foo.com/api/appd/v2/apps/app1" to resolve the application data vs "https://appd.foo.com/api/appd/v2/apps/app1@appd.foo.com".

Service Discovery

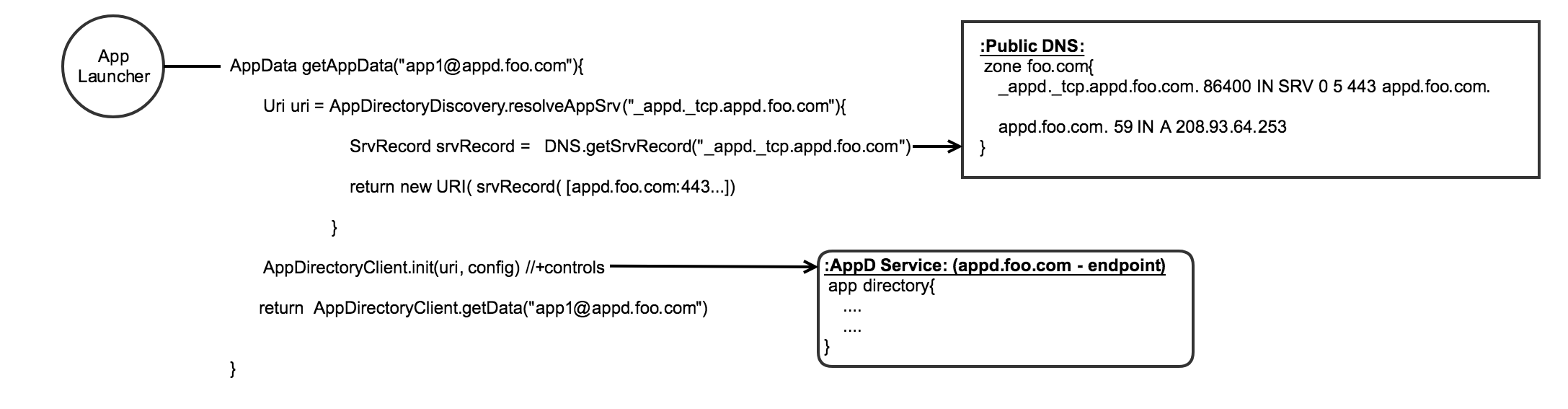

In order to support the discovery of applications that can be used with a Desktop Agent, it is necessary to access data stored in one or more app directory instances.

However, in order to do so, you must first discover the location of an app directory service, which you may then use to generate URIs (e.g. "https://appd.foo.com/api/appd/v2/app1@appd.foo.com") to query a given directory instance for data. In order to construct a URI, the host location and port of a given AppD service instance is required.

Three methods for discovering app directory services are defined in this Standard:

- Static configuration: Statically defined URI records for use within client applications (typically a Desktop Agent implementation) directly.

- Fully-qualified appID namespace syntax host resolution: Discovery of the appD location using a fully qualified application ID (appId) domain name.

- DNS lookup by domain name: Discovery of the appD location using a domain name to lookup DNS SRV records identifying the host server location and TCP port. (RFC2782)

App directory service host discovery implementations SHOULD support each of these methods and MUST support at least static configuration.

Static configuration

As the name implies, a static configuration for an appD service location is defined within a Desktop Agent or launcher application. This is the simplest and most common approach to app directory and application data discovery.

Fully-qualified appID namespace syntax host resolution

An app directory URI can be constructed using a fully qualified application ID (email address syntax) by using fqdn part of the ID as the host location and the name part as the application name. Given an application id "app1" with a fully qualified identifier of "app1@appd.foo.com" an application directory host location can be derived by simply extracting the fqdn "appd.foo.com" from the email syntax. The extracted fqdn "app.foo.com" MUST resolve to the actual host location where the application directory is running.

A launcher can then easily construct a URI by:

- URI protocol is defaulted to

https, but can be overridden by the launcher. - URI hostname is the fully qualified domain of the application ID.

- URI port is default

https/443, but can be overridden by the launcher - URI url is by default

"/api/appd/(version)/apps". Calls that are made without version MUST automatically default to latest, i.e."/api/appd/apps/app1"should return the same result as"/api/appd/v2/apps/app1".

The resulting URI to retrieve application data for "app1" would be "https://appd.foo.com/api/appd/v2/apps/app1@appd.foo.com"

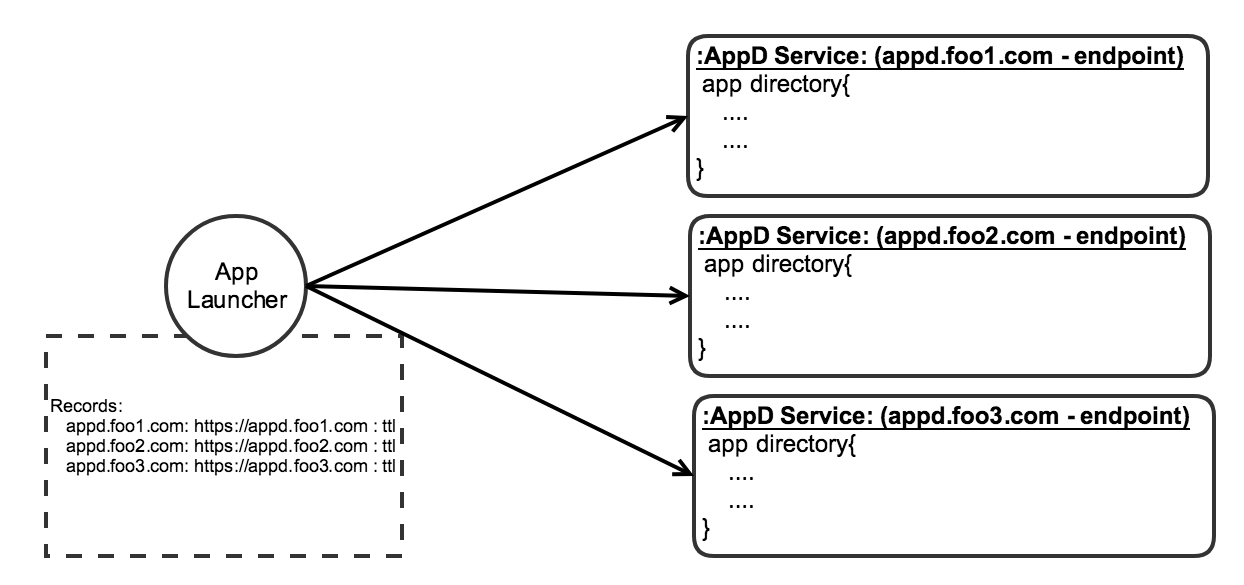

DNS/SRV Records

Another approach to support app directory service discovery (resolution) is through use of existing domain name service (DNS) implementations that are broadly used on the Internet today (see: RFCs). Name service implementations can be considered critical infrastructure and are proven stable with over twenty years of use. Name services can be used both through public Internet or locally deployed intranet, which provides optionality to deployment schemes.

More specifically, resolution of an appD service instance (host location) can be implemented using DNS "service records" (SRV) providing the host instance, protocol and associated port. The following is a well-known description of a SRV record (RFC2782):

zone name { _service._proto.name. TTL class SRV priority weight port target.}

- service: the symbolic name of the desired service. For AppD service, this must be identified as "_appd"

- proto: the transport protocol of the desired service; this is usually either TCP or UDP. For AppD service _tcp must be used.

- name: the domain name for which this record is valid, ending in a dot. For AppD service, the name should directly map to the application identifier domain.

- TTL: standard DNS time to live field.

- class: standard DNS class field (this is always IN).

- priority: the priority of the target host, lower value means more preferred.

- weight: A relative weight for records with the same priority, higher value means more preferred.

- port: the TCP or UDP port on which the service is to be found. For AppD service, TCP should always be used.

- target: the canonical hostname of the machine providing the service, ending in a dot. This would be the host where the AppD service is running.

For AppD Service the SRV record MUST use the following definitions:

- service = _appd

- proto = _tcp

- name = must map to the domain of the application identifier . Example: the name for application identifier "app1@appd.foo.com" would be "appd.foo.com"

AppD service through DNS / SRV records:

Known domains

Although SRV records provide the means of resolving the location of an app directory service for a specific domain, there could be a need to know what domains exist in the universe. This would be a list of domains representing all known directory instances. It is recommended that the FDC3/FINOS organization publish a list of known domains which support AppD services. This publication can be handled in multiple ways, such as structured files or API endpoints. This proposal shall not provide a qualified solution to achieve this, but rather draw attention to a potential requirement.